|

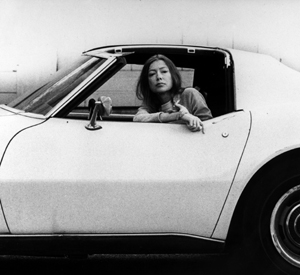

| Joan Didion in Hollywood, 1970 |

I never liked Joan Didion. I have yet to discover whether

this is a controversial statement or not. I’m guessing that it is, given the

amount of “Top 50”/”Top 100”/”Books to Read Before You Croak” lists her work

crops up on.

I read “Play It As It Lays” a couple of years ago and couldn’t

get into it. I found it stylistically irritating and – while I enjoyed the

flourishes of ingenious language and description that abound throughout the

book – I was unable to get beyond this.

Descriptions of characters driving into the “hard white empty core of the world,” for example,

are excellent, and showcase Didion’s talents as a true literary artist. But each

time the book is given a chance to fly, we are dragged back down into the lazy,

languid, mire of Didion’s own narcissism.

You might think narcissism

is the wrong word, that I’m being unnecessarily harsh, but I’ve thought about

this long and hard and found it to be the right word. Joan Didion’s prose is narcissistic

in that the concept of “Joan Didion” – i.e. “the author herself – is always

fully evident within it, staring back at the reader with its ironic, beatnik-ian arrogance.

I’ve read substantially

about the relationship between Didion and her late husband John Gregory Dunne –

who co-wrote the screenplay for the 1972 movie – and have spotted more

than a couple of parallels between the real life ‘Didions’ and the characters

of “Play It As it Lays”. The problem with this sort of dreary gonzo-literature

is that Didion appears to be almost legitimising the actions of a ‘Lost

Generation #2’ (or #3,#4 or whatever number we’re up to now) and denying the existence all other responsibility or obligation.

So, not to put too fine a

point on it, I didn’t like "Play It As It Lays" and I didn’t particularly like

Joan Didion as a person.

Earlier this year, I read “The

Year of Magical Thinking”. My reasoning for picking up this book was that I was

thinking about "Play It As It Lays" one day and was struck with the peculiar

thought that Didion’s self-absorbed writing style would probably translate

rather well to a memoir.

So I went out on a limb,

purchased the book with low expectations, and gave it a go. The thought process

that led me to this book must have been a form of magical thinking in itself,

as I found it thoroughly compelling from the outset.

For those who are unaware,

The Year of Magical Thinking deals with Joan Didion’s own experience of the

sudden death of her husband and its immediate aftermath. It is also grimly capoed

by the death of the couple’s daughter shortly after the book was completed, an

event which would be dealt with in a second book, “Blue Nights”.

Maybe it is the grim and

sobering subject matter of the book that finally brings Didion – now an elderly

lady – into the realms of sympathy and normality, or maybe it is that – with Didion

in this newly reflective frame of mind – the author is able to write more

candidly about her own failings and her own issues, rather than retreating into

the superficial constructions of her fiction.

In the book, Didion deals

with death head-on, often more bluntly than many of her fellow authors. Those

whose literary diet began with the stoicism of Hemingway will be fascinated by

the way that Didion’s grief is personified to such an extent that it almost

becomes an additional character in the book, as well as the way in which she accommodates

the insanity this monstrous grief brings.

Unflinching and reflective

in its portrayal of Didion’s relationships with both her husband and her

daughter Quintana over the years, "The Year of Magical Thinking" is made even

more poignant by the reader's prescient knowledge of Quintana’s imminent and

untimely death following intensive brain surgery in 2005.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" is literary redemption for Joan

Didion, in the most heartbreaking and brutal fashion.