The Bildungsroman, or coming of age novel, has been done into the ground. As universal as breathing air, or eating food to stay alive, the concept of “coming of age” is something each of us can relate to, and so the Bildungsroman has become a well-worn and well-trodden novelistic form, almost to the point of cliché.

If there is one writer whose work can definitely not be described as clichéd, it is James Joyce. Joyce’s modernist masterpiece, "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man", is my nomination for the title of “Ultimate Bildungsroman”.

While anticipation continues to grow over Sunday’s Sports Personality of the Year Award, I’m holding my own little ceremony in my head. Not populated by Olympians and sporting greats – well, not many – the nominations list for Ultimate Bildungsroman features some of the literary titans of the past 250 years.

You probably have your own ideas about what deserves to go on this list: "Catcher in the Rye"? Definitely. "Tom Jones"? No list would be complete without it. "William Meister’s Apprentice" by Goethe? Possibly, I’ve never read it. But, as this blog is run entirely undemocratically, it is "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man" that takes the prize.

Originally sketched out in 1905 as "Stephen Hero", "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man" finally saw light of day when it was serialised in The Egoist in 1914 before its release as a complete novel two years later.

It is "A Portrait…"’s famous first sentence that frames the novel’s Bildungsroman credentials;

“Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road…”, writes Joyce, dropping the reader directly into an infantile world of onomatopoeic lexicon and minimal punctuation. We then learn that this is a story told to young Stephen Dedalus – the novel’s protagonist – by his father Simon, a figure seen only through glass and described as having “a hairy face”.

The opening is the author's perfect evocation of childhood, something that Stephen Dedalus almost immediately begins to drift away from. Within a few pages, Stephen is attending boarding school at Clongowes, and by page 100 we are told that Stephen’s memories of childhood are already fading from his mind. This is Joyce’s comment on the unreliable fluidity of human existence and a rejection of the snapshot realism favoured by authors from the previous century.

Compare this startlingly childlike opening with the discussions of philosophic truth found later in the book and you begin see the vastly expansive scale of Joyce’s take on the Bildungsroman. Or – more appropriately – his take on the Künstlerroman, a novel charting the intellectual development of an artist.

It is this enormity of scale that elevates "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man" beyond the standard constraints of the Bildungsroman, into a plane far removed from the thematic concerns generally associated with the form. Weighty matters such as spirituality and nationalism are all dealt with on young Stephen’s journey into adulthood; two concerns which form key parts of any true intellectual development.

One passage in particular draws parallels with Salinger’s "Catcher in the Rye", written several decades later and often held up as an archetype of the Bildungsroman form. This is the passage dealing with Stephen’s first encounter with a prostitute, during which he is unable to kiss her and expresses his desire to be “held firmly in her arms”. While Stephen does eventually give in to the “swoon of sin” – unlike Holden Caulfield – it is this tender naivety of youth that sets the reader up for an acceleration in Stephen’s slide towards adulthood.

Having tasted sin and therefore forsaken eternal life in heaven, Stephen finds that “no part of his body and soul had been maimed but a dark peace had been established between them”. This is the crux of Stephen’s development towards academic, philosopher and artist, wrestling with the constraints placed upon him by the rigididity of Christianity and nationhood.

I could continue, picking out passage after passage from Joyce’s work and analysing it in detail, but I think I’ve put my case forward plainly. Whoever claims that coveted SPOTY crown on Sunday night, "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man"’s place as the pinnacle of the Bildungsroman genre is assured, for the time being at least.

Sunday 16 December 2012

Thursday 27 September 2012

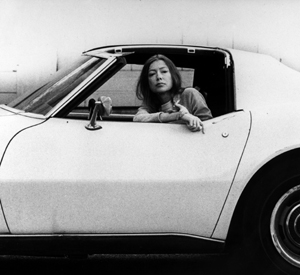

Joan Didion: Fiction v Non-Fiction

|

| Joan Didion in Hollywood, 1970 |

I never liked Joan Didion. I have yet to discover whether

this is a controversial statement or not. I’m guessing that it is, given the

amount of “Top 50”/”Top 100”/”Books to Read Before You Croak” lists her work

crops up on.

I read “Play It As It Lays” a couple of years ago and couldn’t

get into it. I found it stylistically irritating and – while I enjoyed the

flourishes of ingenious language and description that abound throughout the

book – I was unable to get beyond this.

Descriptions of characters driving into the “hard white empty core of the world,” for example,

are excellent, and showcase Didion’s talents as a true literary artist. But each

time the book is given a chance to fly, we are dragged back down into the lazy,

languid, mire of Didion’s own narcissism.

You might think narcissism

is the wrong word, that I’m being unnecessarily harsh, but I’ve thought about

this long and hard and found it to be the right word. Joan Didion’s prose is narcissistic

in that the concept of “Joan Didion” – i.e. “the author herself – is always

fully evident within it, staring back at the reader with its ironic, beatnik-ian arrogance.

I’ve read substantially

about the relationship between Didion and her late husband John Gregory Dunne –

who co-wrote the screenplay for the 1972 movie – and have spotted more

than a couple of parallels between the real life ‘Didions’ and the characters

of “Play It As it Lays”. The problem with this sort of dreary gonzo-literature

is that Didion appears to be almost legitimising the actions of a ‘Lost

Generation #2’ (or #3,#4 or whatever number we’re up to now) and denying the existence all other responsibility or obligation.

So, not to put too fine a

point on it, I didn’t like "Play It As It Lays" and I didn’t particularly like

Joan Didion as a person.

Earlier this year, I read “The

Year of Magical Thinking”. My reasoning for picking up this book was that I was

thinking about "Play It As It Lays" one day and was struck with the peculiar

thought that Didion’s self-absorbed writing style would probably translate

rather well to a memoir.

So I went out on a limb,

purchased the book with low expectations, and gave it a go. The thought process

that led me to this book must have been a form of magical thinking in itself,

as I found it thoroughly compelling from the outset.

For those who are unaware,

The Year of Magical Thinking deals with Joan Didion’s own experience of the

sudden death of her husband and its immediate aftermath. It is also grimly capoed

by the death of the couple’s daughter shortly after the book was completed, an

event which would be dealt with in a second book, “Blue Nights”.

Maybe it is the grim and

sobering subject matter of the book that finally brings Didion – now an elderly

lady – into the realms of sympathy and normality, or maybe it is that – with Didion

in this newly reflective frame of mind – the author is able to write more

candidly about her own failings and her own issues, rather than retreating into

the superficial constructions of her fiction.

In the book, Didion deals

with death head-on, often more bluntly than many of her fellow authors. Those

whose literary diet began with the stoicism of Hemingway will be fascinated by

the way that Didion’s grief is personified to such an extent that it almost

becomes an additional character in the book, as well as the way in which she accommodates

the insanity this monstrous grief brings.

Unflinching and reflective

in its portrayal of Didion’s relationships with both her husband and her

daughter Quintana over the years, "The Year of Magical Thinking" is made even

more poignant by the reader's prescient knowledge of Quintana’s imminent and

untimely death following intensive brain surgery in 2005.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" is literary redemption for Joan

Didion, in the most heartbreaking and brutal fashion.

Thursday 20 September 2012

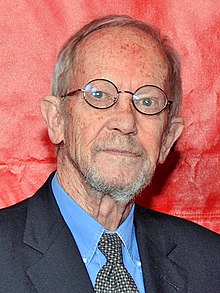

Elmore Leonard wins Lifetime Achievement Award

Novelist Elmore Leonard – the skilful crime writer who

produced such high-paced classics of the genre as “Out of Sight” and “Rum Punch”

– is to become the latest recipient of a prestigious lifetime achievement

award.

The 86 year old will receive the National Book Foundation’s

Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, in New York on

November 14th.

In receiving the coveted – if slightly longwinded – award, Leonard joins a list of luminaries that includes John Updike, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe.

In receiving the coveted – if slightly longwinded – award, Leonard joins a list of luminaries that includes John Updike, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe.

After the news broke, Leonard answered questions about the

award with characteristic humility;

"I was very surprised,” he said. “I didn't ever count

on winning this kind of an award; I’ve won a lot of awards but not like this

one.”

Leonard is expected to make a speech at the National Book

Awards on the same evening, the organisers of which are requesting her trims

down to only six minutes. We’ll see if he manages to adhere to such a

limitation.

Tuesday 18 September 2012

“Hamsun Was a Nutcase”: Why It’s Not Always Necessary to Agree With Someone’s Politics to Enjoy Their Work

| |

| Hamsun on the cover of "Hunger" | ("Sult") |

For many years, Hamsun – an author often cited as the originator of the modernist movement and an undeniably brilliant and innovative writer – was shunned as a Nazi sympathiser and his work largely ignored by a country still scarred by the effects of German occupation during the Second World War.

Now attitudes are changing. Hamsun’s work is gradually creeping back into the classrooms and libraries of Norway and is slowly but surely becoming a more acceptable subject for discussion or even appreciation.

But does this softening of attitudes represent a natural and sensible view of the work of a man now consigned to the annals of history? Or does it symbolise an apathetic response to the sorts of far-right views and extremist politcal values that Anders Breivik has brought back onto the national agenda?

History does not record Hamsun as a particularly good person. Attempts to play down the Nazi ravings that characterised Hamsun’s later life as the baseless ramblings of someone deep in the grips of mental illness are discredited by his description of the USA as “a mulatto studfarm” as early as 1889, when the author was only 30 years old and in the first flushes of his creative brilliance.

Hamsun’s view of himself as a member of an intellectual elite led him to despise the egalitarian politics of the left and instead embrace the cause of the fascists during World War I. He became a member of the notorious Nasjonal Samling party that would later seize power in Norway during World War II and even wrote a passionate eulogy for Hitler after his death in 1945, only escaping execution for treason after the war by being declared psychologically unsound.

So no, Hamsun was no angel. In fact, the man was downright abhorrent. But does this render works like “Hunger” (published in 1890) worthy of deletion from literary history?

“Hunger” is an exceptional piece of work. Following a struggling journalist as he traipses around Oslo in search of food, work and self-respect, this short, searing and devastatingly visceral novel represented a step away from the realist traditions of the 19th century and laid the groundwork for what would become the modernist movement.

Hamsun’s literary manifesto is clear: writers should only concern themselves with a character’s own, inherently flawed perception of the world around them; presenting that world in terms of cold hard fact is boring and disingenuous. Without Hamsun, it’s debateable whether the work of Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner or any of the other totemic writers of the first half of the twentieth century could have developed in the way it did.

Hunger remains a stunning portrayal of the strange experiences and bizarre rationale of a man on the edge. Think “Post Office” transposed to Scandinavia in late Victorian times on you’re on the right track. Whether or not you agree with the class politics or racial prejudices of its author – none of which are touched on in the novel – Hunger remains a fascinating book.

As human beings, we should trust ourselves enough not to be so swayed by the argument of another that we lose touch with our own principles and convictions. We should be able to expose ourselves to views we do not agree with, without fear of succumbing to some sort ideological radiation poisoning.

When we specifically select our reading material based upon what we think our principles are, we are in serious danger of prejudicing ourselves and reinforcing the rigidity of our thought processes. Strong convictions will stand up to any test; reading Knut Hamsun will not turn you into a fascist. Unless you are one already, of course.

Lermontov, Pushkin and Byron – The Original Superfluous Men

| |

| A youthful looking Mikhail Lermontov |

The superfluous man is one of the lasting legacies of

Russian literature in the 19th century. The phrase – referring to a peculiar

individual, undoubtedly gifted but tortured and existing outside the practical

bounds of society – was coined by Ivan Turgenev in the title of his 1850

novella “The Diary of a Superfluous Man”, but the roots of the concept stretch

further back in time.

The origins of the concept of the superfluous man are so

fitting that they are almost predictable. The formation of its constituent

parts began in the mind of – you guessed it – Lord Byron; in many ways the

archetypal superfluous man himself. Byron’s narrative poem, “Childe Harold’s

Pilgrimage” was published over 30 years before Turgenev’s famous work and is

widely credited with sowing the seeds of the superfluous man character in the

Russian literary consciousness.

It was Alexander Pushkin who first took the idea of the superfluous

man back to Russia, using Byron’s work as the inspiration for his own famous

narrative poem, Eugene Onegin. Onegin is a suitably Byronesque dandy from Saint

Petersburg, who cobbles together his own ‘individual’ personality from various

literary tropes and ideals.

If Pushkin and Byron laid the groundwork for the character

of the superfluous man, it was Mikhail Lermontov who cemented its place in the

Russian literary canon. Born in 1814 to an aristocratic family, Lermontov was

an artistic prodigy, producing poetry, stunning landscape paintings and prose

while barely in his 20s.

It was in 1839, when aged only 24, that Lermontov completed the

work that would crystallize the character of the superfluous man, “A Hero of

Our Time,” a novel which elucidates the life of its central character,

Pechorin, through the eyes of a number of witnesses to his deeds.

Apart from both being prime exponents of one of Russian

literature’s most enduring devices, the parallels between the lives, careers

and deaths of Pushkin and Lermontov are eerily apparent. Both “Eugene Onegin”

and “A Hero of Our Time” describe a duel between the protagonist and another

character; both Pushkin and Lermontov came to untimely ends while participating

in a duel.

On July 25th 1841 the dashing, swashbuckling army

officer Mikhail Lermontov engaged in a duel with another officer, Nikolai

Martynov, whom he had offended. Martynov shot Lermontov dead; the writer was

26 years old.

In many ways, Mikhail Lermontov, Lord Byron and Alexander

Pushkin represent the archetypes that have made the idea of a superfluous man

so enduring throughout the development of modern culture. The

live-fast-die-young-leave-a-beautiful corpse attitude has pervaded into some of

the most famous and evocative cultural iconography of the 20th and

21st centuries.

James Dean, Marilyn Monroe and Kurt Cobain are all more

modern examples of the superfluous man – and woman – concept made flesh, of

people whose disorders made them brilliant but crucially incompatible with real

life.

Criticised by some as symptomatic of arrogance and an

inability to “pull yourself together”, but embraced by others as a fascinating

critique of social convention, the superfluous man concept will continue to be relevant

as long as society continues to impose its restrictive framework onto ordinary lives.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)